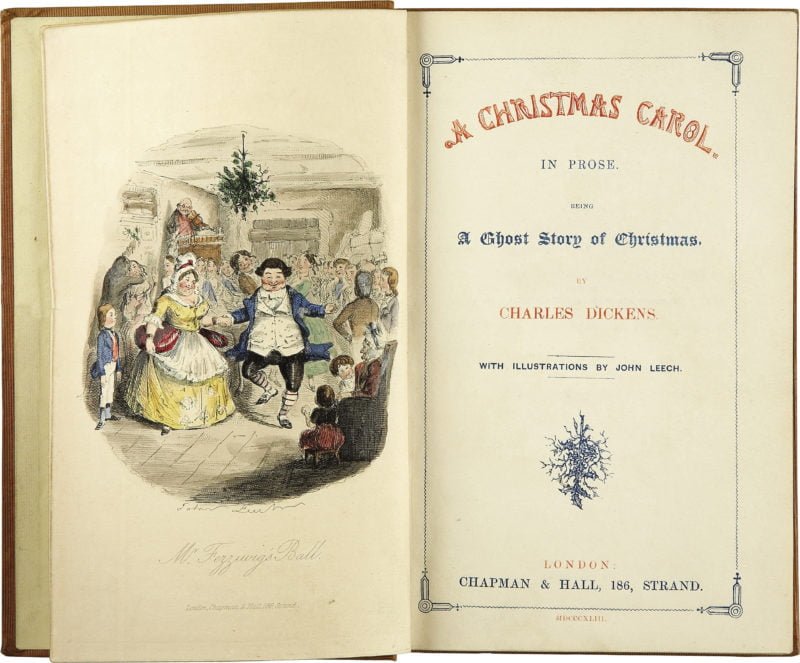

We cannot leave Christmastide without a word about literary Christmases! Every year the hallowed books come out: Mr. Willowby’s Christmas Tree, a Little House Christmas, the Grinch, a Charlie Brown Christmas (the adult Lucy is selling real estate in the Vail Valley today), various Nights Before Christmas, Rudolph and of course, Charles Dicken’s beloved Christmas classic A Christmas Carol.

I cherish reading these various versions of holiday joy, each a shade of parable commenting upon the conversion of the heart constitutive for any believer. But Dickens must be awarded a special place. Were it not for former giants of English verse like Bard William Shakespeare and Scottish Poet Laureate Robert Burns, Dickens would stand even taller. His frequent illumination of and harsh critique of Britain’s Victorian class stratification is immediately evident in Carol, juxtaposing Scrooge’s parsimonious, accumulated but stagnant wealth with the Cratchits’ penurious but dignified, compassionate poverty. But Dickens accomplishes this task elsewhere. No, there is much more to Carol than Victorian critique. Ebenezer’s journey (a biblical name, Hebrew for stone of assistance) is distinctly a transformation and expansion of the heart even more than old Grinch, departing from the musty death of pursuing wealth above all to receive a transformed life with both blood and adoptive family in his life’s last chapter.

I dare anyone to read those final paragraphs of Carol out loud and remain unmoved by Scrooge’s dramatic conversation to a empathetic and compassionate life. Biblically, Dickens charts a shift from “may your money perish with you” to “well done, good and faithful servant!” Christmas time is simply a convenient plot device to serve as literary backdrop! The elements of transformation, you ask? Well, er, uh….first, pain of memories involving loss, guilt and regret. Richard Rohr argues persuasively that life itself involves pain in the first half, but that pain can propel us to tremendous growth and transformation in life’s second half. M. Scott Peck thought so also, as did Thomas Merton, Henri Nouwen and just about any other spiritual writer in the last 100 years! But Dickens knew it long before; Scrooge must confront his life’s regrets and woundings in order to change. Next, empathy towards the pain of others. Scrooge actually asks the Ghost of Christmas Present if tiny Tim will live! Francis of Assisi’s famous prayer mentions seeking first to understand before expecting others to understand us. Jesus healed many from the deepest well of existential empathy for their suffering. Empathy stretches our hearts to grow those many sizes larger than they were before. Then, legacy. Scrooge asks Christmas Future timidly if anyone is impacted emotionally by the death of the man he is auditing, and the answer is rough. A funeral attended only by those paid to be there. “Finally, acceptance and restoration. Old Screw accepts his entire life and his own collusion with pain, trauma and bitterness while seeking to make amends with God, his remaining family and the astonished Cratchits. Scrooge also receives a beautiful sense of gentle humor about his previous failings, able to laugh with others about his life.

Dickens isn’t simply weaving an entertaining Christmas tale to distract his Victorian audience from their horribly stratified world. No. Dickens is preaching a parable of Christian transformation, and it’s a good one! May God bless us all, every one!”